What does it mean to bear witness? We’re often taught that to know something that has happened is to rely on what is left for us over time, and that these vestiges hold some communication, however subtle, from the past. For the ones who find comfort that whatever has passed into history sits patiently in the background to be poked, prodded, scrutinized, it reinforces the belief that history is passive and its crystallized contents to be objectified by our ignorance, on our schedule.

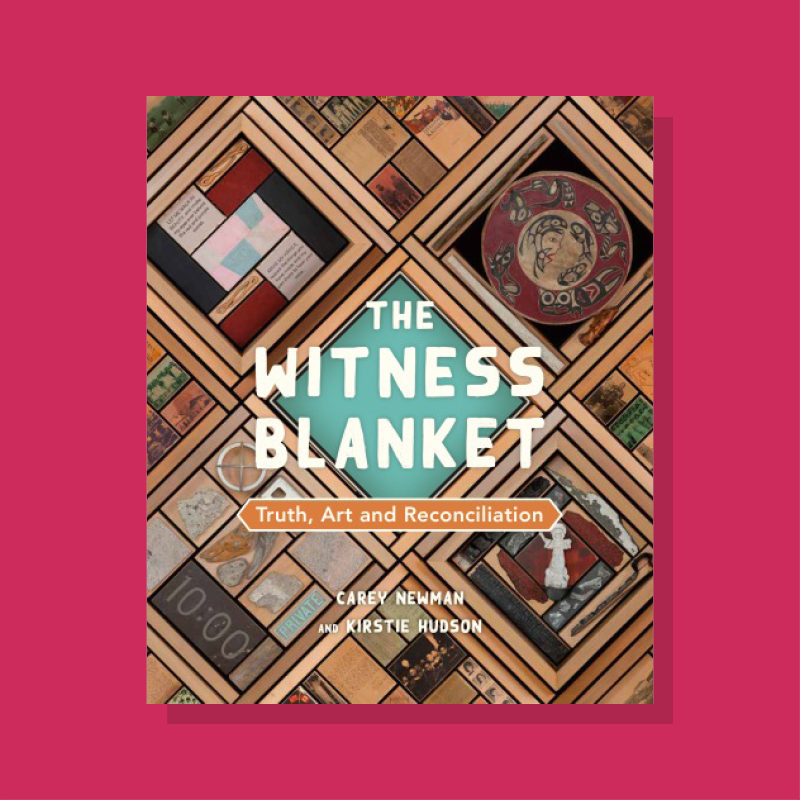

Festival authors Carey Newman and Kirstie Hudson’s The Witness Blanket: Truth, Art and Reconciliation challenges us to think about history (a shameful piece of national history) as something we should be present for, whose manifestations through pride, joy, trauma, and erasure continue intergenerationally. The book examines the installation The Witness Blanket (currently at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights) that Newman and his team created: a monumental project sourcing materials from all of Canada’s residential schools weaved into a three-dimensional blanket, an object whose significance in Kwakwaka’wakw and Coast Salish cultures include veneration and protection. Newman notes that his role “as an artist is to bear witness,” and that we are all – from the objects to the audiences – bearing witness in some form.

Many objects have shared histories, some deeply traumatic and others buoyant with hope, and are grouped in such a way in the various chapters on the lives and experiences of children in residential schools. I very much enjoyed Chapter 6 (Kids Will Be Kids), where we see children passing their time and finding communities within their displacement. It’s hard to hold the heinous aspects of residential schools with the joys we see in some of these photographs and objects, and I find the dissonance uneasy at times. However, what is clear is the resilience of these children, a testament to how survival of an individual and of cultures always finds a way.

Above all, the most poignant section was Chapter 3 (I’m Hungry) on the conditions of food and nutrition in residential schools. Not only were familiar foods banned in these schools as one of the many ways traditional ways of living were stripped from these children, the food that they were given were portion-wise not enough and below nation-wide nutrition standards to sustain healthy developmental growth. The ways that children had to make do with what was available and the punishments relating to food continued into their adulthoods and were further transferred when they themselves became parents. I’ve read instances of food insecurity many times in the works of Indigenous writers here in Canada both as a product of residential school abuse and the capitalist consequence of food deserts in areas with disproportional Indigenous, Black, and other racialized populations. Yet, this chapter still affected me deeply because of the ways the children showed each other the care and nurture that were so disgustingly absent in the adults who withheld from them.

The centre of The Witness Blanket is a white door taken from the boys’ infirmary at St. Michael’s residential school in Alert Bay, British Columbia. By installing this door as the centrepiece of The Witness Blanket, Newman had to navigate the many meanings it held. As a part of the infirmary, it held the significance where children who needed their parents and communities the most were denied healing that they deserved. As a physical object whose cultural function is to separate, to enclose, to hide, it symbolized the very denial of the abuses and trauma the colonial institutions upheld. Newman noted that he wanted at least some part of The Witness Blanket to be touched, held, interacted with, and for viewers to be able to open and close this door creates a sense of connection to the overall work and experiences of residential school survivors. It also returns an agency denied to Indigenous peoples in Canada, where they now can control whether and when to give closure to a past still so much relived.

In each chapter is a section called “Woven In” where Newman ties personal and familial experiences to the work, especially those of his father, Victor Newman, a residential school survivor who attended the Sechelt residential school and St. Mary’s residential school. In Chapter 8 (More Than 100 Years), Newman pays tribute to the braids in the Witness Blanket in a haircutting ceremony for his sisters Marion and Ellen. Of particular note is once again on the white door: two small handprints about hip level from Newman’s daughter Adelyn, “symbolically holding it open.”

This is a book that should be a staple to any school library and classroom to counter the archaic ways of teaching history and social developments using pedagogies that centre material history, Indigenous experiences, and kin networks. The images and text are robust, but are organized into chapters or sections of the Blanket that are easily digestible for children in middle and high school grades. It is also a pivotal supplement to any humanities and social science class because it takes care to illuminate Carey’s artistic practice, familial history, Canada’s social and political transformations, and intergenerational storytelling. It also takes great care to remind all of us of all ages that history is not to gaze, but to be seen, not only to remember, but also to be present for.

The Witness Blanket continues as a travelling exhibition, currently in Kwanlin Dun Cultural Centre in Whitehorse, Yukon. It returns to British Columbia in January 2024 at the West Vancouver Memorial Library. I strongly recommend learning about or deepening your understanding on the subject matter of The Witness Blanket before then with the website of the archived exhibition at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, the artwork’s website, and the iOS app for the exhibition.

We welcome you to share your learnings, insights, and questions with Carey and Kirstie when they are here for their events for middle grade and high school students at the Vancouver Writers Festival.

— Sarah Wang, Programming Coordinator