This is a very peculiar book because, although short, it has stayed with me, and my mind repeatedly wanders into the unfamiliar territory of animals with very human experiences and dispositions. It is a picture book that flips quickly, and couldn’t be more straightforward in narrative structure, yet in its abundance of negative space stew the mysterious intentions of the characters. After the last page, I was obsessed. I read and re-read, looking for clues in its soft washes of colour and the mise en scène of the characters. I was not satisfied with the conclusion. There had to be something more, something deeper at play here. This is not just about a hat. It cannot simply be about a hat.

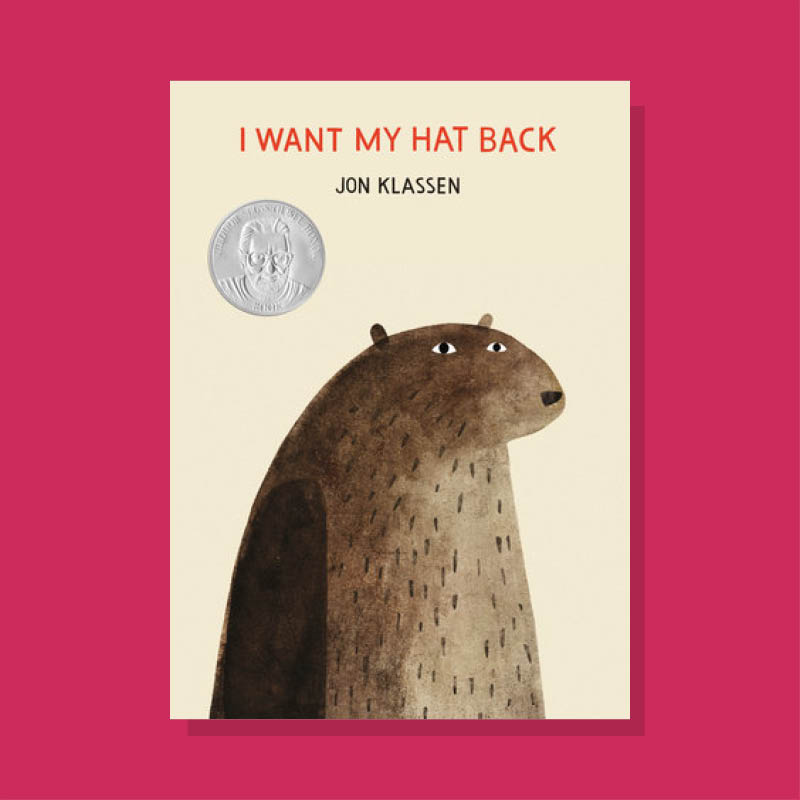

We don’t dillydally at the beginning. I admire the opening conviction. It is established that a hat is missing and our central character, the bear, wants to reclaim it. In the subsequent pages, the bear encounters various other animals – a fox, a frog, a rabbit, a turtle, a snake, and what could be an armadillo or a mole – and each respond (the text colour corresponds to the colour of the animal) in their idiosyncratic ways, some directly, others with details or metaphysical retorts. A two-page spread follows where the bear, now prostrate, experiences an acute bout of depression, until a giraffe asks the bear to describe the hat. Up until this point, the illustrations are akin to crunchy Scandinavian design trends of the past decade. As the bear’s descriptions allow it to recall an earlier scene, the illustration becomes a 1970s giallo-esque shock while the text grows to menacing capitals. We return to the rabbit, who is still wearing the pointy red hat just pages earlier. Accusations are thrown and the hat exchanges heads. A squirrel stops by to inquire about this ownership transfer and the bear now displays not only the accessory but also a similar temperament and pattern of speech as the rabbit.

Many things are amiss here. Why is the bear upright? What is the occasion for a hat shaped like a birthday celebration headpiece? Is or was there a party nearby? Another eerie note is that none of the characters look at each other in the eyes, until the final staredown. Maybe they are shy, or maybe they are all co-conspirators.

I’m sure the CIA would explain that the rabbit’s initial response was textbook guilty behaviour. When asked if it had seen the bear’s hat, the rabbit objected, projected, and deflected. To mitigate specific guilt, the rabbit anticipated a universal rejection of seeing “any hats anywhere.” Mendacity lies in the verbose.

At the end of the book, the rabbit is gone, the bear, now seated, is in its place wearing the hat. The rustled leaves and branches suggest a struggle. When asked a question of what the bear may have seen, the bear now objects, projects, deflects. While natural law may dictate the bear to be the victor, I propose another theory.

The rabbit is hiding in the bear. Perhaps the rabbit isn’t even the original thief and its body then became host to this sinister hat burglar, every iteration adding a new layer to this matryoshka of millinery enthusiasts. This could also just simply be a symbol of capitalist greed, where the dehumanizing aspects of private ownership and scarcity rely on violence and intrigue to reinforce consumer behaviour. Why not have it be Freudian, where unconscious aggression overcomes the superego’s acquiescence of the social protocols of truthfulness, etiquette, and proper dress?

I then remembered that this is a children’s book, and the simplest explanations are often the best. Children, everywhere and since the beginning of time, have lost things that are important to them. Animal counterparts lack the digital dexterity to Sharpie their names onto personal belongings. But every creature can experience the simple pleasure of reclaiming what is theirs. A hat is a hat, we should just let that be that, and don’t ask any more questions.

— Sarah Wang, Programming Coordinator