President Biden has been busy lately. He has a tampon shortage. He is fist-bumping across the Middle East. Admittedly not his own gaffe, but the beloved First Lady was criticized by the National Association of Hispanic Journalists (NAHJ) for comparing Hispanic pride and diversity in the United States to “breakfast tacos”. These are just the intermissions to the ongoing crises of bodily autonomy for American women, BIPOC, and LGBTQ+ communities; gun and police violence; and the continental drift-like shenanigans of partisan mudslinging.

Before I continue, I want to first preface this by saying that there are some people and things so sacred to me that I exhibit Gollumesque qualities of wanting to venerate, preserve, and protect. Hannah Arendt is one of them. It pains me to have to bring up her work during this time – of course, Hannah has transcended time and her work is relevant indefinitely – because I almost feel it is a disservice to, it is crass to hold her work in such an environment of people, events, and things we would rather sweep into the dustbin of history. We are not worthy to pull her from our collective records of human achievement in today’s shameful state of affairs.

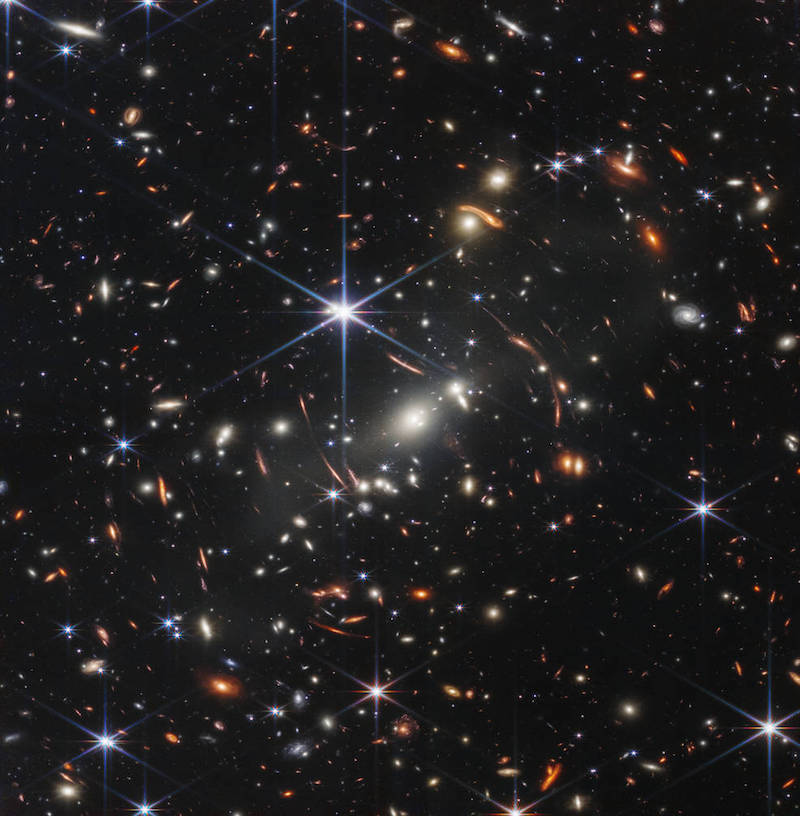

Why does this matter? Earlier this week, President Biden gave the world the James Webb Space Telescope’s deepest infrared image of the universe, a look of galaxy cluster SMACS 0723. It is our most detailed view of the earliest of the universe, an idea that is almost incomprehensible when compared to its actual scale: “a patch of sky approximately the size of a grain of sand held at arm’s length by someone on the ground.”

If anyone has trouble feeling grounded after this image, I urge them to meditate on Arendt’s prologue to The Human Condition (1958) and the subsequent essay “The Conquest of Space and the Stature of Man” (1963). Upon first reading the prologue a decade ago, I had never felt more alienated to my own earth-bound condition. I wanted, profoundly, to have existed in 1957 when the Sputnik was launched or in 1961 when cosmonaut Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin entered where no man had before, not only so that I could bask in the schadenfreude of American unexceptionalism, but so that I could also witness, and perhaps experience, this collective anthropological approximation to the Archimedean point.

The frivolousness of humanity is nothing new. Our earliest ancestors deified their own creations, the way we still deify our postmodern materials. This is our nature, perhaps the only disposition that has withstood the seemingly infinite rounds of natural selection. We laud our subjective existence with our grasp of the objectivities of science, and our technological innovation as our emancipation from the lower species, and perhaps even tools to subjugate natural laws we have yet to conquer.

We know of our place in all of the universe. We know of the tiny suspended “pale blue dot”. Using the human body as a symbol for the entirety of time, we know that one swipe of a file on one of our nails “[wipes] out all of human history (and more).” To neutralize our hubris, we know that we did not create the universe. Maybe it’s the schadenfreude of my age: to be in awe of the tech bros who still believe they can be the ultimate creator. However, man’s industry is in its instruments. That we can create, and the James Webb Space Telescope (a joint project with NASA, the European Space Agency, and the Canadian Space Agency) is undeniably a marvel for us laypeople, and an upgrade for the scientific community relying on other aids like the Hubble Space Telescope.

Is birth the ultimate conquest? We missed our conception, but through this week’s infrared image, we can witness our earliest afterbirth. It is difficult to reconcile this monumental achievement of seeing what was over thirteen billion years ago to the momentous human-made calamities closer at home today.

Thus, the instrument is the intermediary. I wonder if the Telescope yearns for the hands that created it and the home it was ejected from. I wonder if it will return. I wonder if it feels alienation more so than what we feel on Earth. I wonder if the human, in the sense of our “stature”, matters at the end of time. Birth, like all creation, is a matter of division, a departure from our creator. May we never lose our wonder at our position in all of this, no matter how infinite or infinitesimal.

———-

I am grateful to Professor Victor Falkenheim who first read my reflections on how deeply Hannah Arendt’s writings on the human condition affected me. At the time, the only thing that I could see outside my window was the brutalist heaven that is Robarts Library. Today, I see much more.

— Sarah Wang, Programming Coordinator