I was first introduced to the work of Emory Douglas while writing my senior thesis to complete one of my majors in art history. My research was on how foreign bodies were used to visualize international solidarity and China’s alternative leadership in the transnational socialist movement in the early years of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. To say it was an ironically iconic time would be an understatement: despite the predominance of isolationism and domestic upheaval, state propaganda, particularly in its poster form, “screened” expansive visions of racial fraternity in the service of ideology. These anonymous artists are mostly remembered by the few images of art school students in a more proletarian Pollockian stance, presenting an edification that was dictated to them. I could never fully satisfy my analysis because any study of production begets the problem of consumption and the medium of the poster, coupled with the turmoil and erasures of the time, prevented a full understanding of who saw these images, how did they understand their international brothers if they have never left their national borders? The only evidence of consumption I found in my research was across the ocean, images of the Chinese people’s struggle, often personified to the icon of Mao itself, on the walls of the Black Panther Party’s office in Oakland, California. It was a stunning, coming full circle moment. I grew up in the Bay Area and remember absolutely no mention of the BPP in any part of my education.

Emory Douglas served as the Minister of Culture in the Black Panther Party and managed the layout, printing, design, and art of the BPP’s newspaper, The Black Panther, the major communication platform of the Party’s ideology, programs, and news. During the early years of the Party, The Black Panther had a circulation of several hundred thousand weekly copies in the United States and abroad. Beyond my own intrinsic interest, Emory Douglas was a single name, whose work had a known audience and produced recorded feedback, and, most pivotal in any understanding of social change, depicted reality rather than an imagined myth.

The art history establishment has historically struggled with what constitutes art (case in point, my faculty was named Fine Art History), and if the disciplines of design, advertising, and illustration were seen as the ugly stepsiblings, propaganda is that “uncle” to whom no one wants to claim relation and of whom nobody invited to the gathering. Because its iconography is so familiarized and signifiers explicitly agitate, propaganda is dismissed as romantic, dogmatic, convenient. I think this is where so many unnamed artists who have created in this field should be getting credit as this is precisely the point, particularly when looked at through the lens of advocacy. Colette Gaiter, Associate Professor of art at the University of Delaware, notes Emory’s fluency in “[making] previously radical ideas seem normal and universal”.

While this taming of the acerbity of revolution may feel like an ode to the more mainstream Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, several contributors of this volume intimate that the BPP’s communication was fundamentally different because they were talking to the oppressed, not the oppressor (and perhaps the most critical, not to the perceived “liberator” – the white, middle-class, liberal ally). Emory’s imagery was immediate (collages with photographs and recognizable and timely symbols, alongside placement of most recent news and programs of the BPP), fomenting (porcine caricatures of the main enemy of the people – the police), and porous (the volume provides side by side comparisons of various propaganda images from around the region and the world including messages and designs from the Viet Cong, Cuba’s OSPAAAL, and Chicano activism). Throughout all of these declarations, there is no plea, no request of integration, equality, justice. There is only the message that the oppressed, regardless of race, origin, or language, understand too well: self-determination and self-preservation.

This volume is a monograph of Emory’s work with the BPP and includes several essays by members of the Party influenced by his work, those who worked alongside him, and those whose own work carries the torch today. Those who knew Emory are almost unanimous in their description of his laid-back, quiet personality, whose keen observations are explosive in print. Years later after the dissolution of the Party, Emory, in the final section of the book during an interview with St. Clair Bourne, upholds that “all art was a reflection of a class outlook. Which is true, even today”.

And what a time “today” is. The inflammatory reactions against Critical Race Theory, the perennial spectre of police brutality, what happens when these images become benign? What happens when the revolutionary becomes the mundane? My interest in this matter stems from this internal rage that the most basic of human decency must be persuaded – or to borrow the word of Colette Gaiter, shouted – as if its application is somehow against nature, that somehow the very presence of a fellow man is not sufficient for the kind of fraternity that even animals we deem lesser than our own kind demonstrate without any hint of trepidation. My questions remain: was there a dialogue? Could those far away who wanted to support, hear? Could those who were close enough to hear, listen?

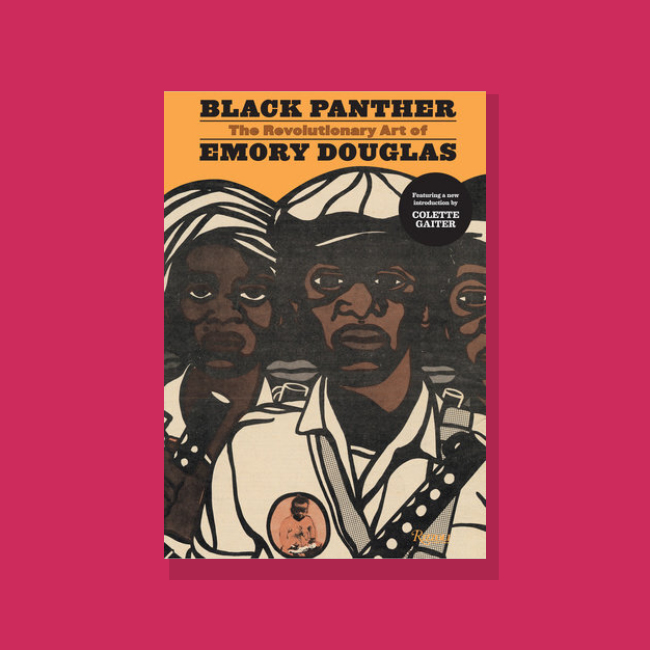

Black Panther: The Revolutionary Art of Emory Douglas was published in 2014 by Rizzoli New York, with contributions by Emory Douglas (former Minister of Culture of the Black Panther Party), Colette Gaiter (current associate professor of visual communications in the art department of the University of Delaware), Bobby Seale (co-founder, with Huey Newton, of the Black Panther Party), Danny Glover (actor, producer, director), Kathleen Cleaver (attorney, author, and senior lecturer at Yale University and Emory Law School, and former Communications Secretary of the Black Panther Party), Amiri Baraka (writer, poet, essayist, critic), Sonia Sanchez (poet, writer, and professor) and edited by Sam Durant (multimedia artist). It is currently out of print but available at local libraries.

— Sarah Wang, Programming Coordinator